Localizing a Dark Fantasy Text-Adventure Game: Technical Workflow & Design Choices

Game Demo

Slides (Onedrive):

Note: The following content is generated from a live presentation transcript, so it may read more like spoken language than a polished article.

Slide 1

Good afternoon, everyone. I’m happy to present my localization process and outcomes for the game “A Dark Forest.”

Slide 2: Introduction & Overview

This project was a four-week endeavor from November 8 to December 6. Today, I’ll walk you through the project’s objectives, workflow, technical choices, translation methods, and the in-game testing process that ensured my localization aligns closely with the game’s immersive, text-driven design.

Here’s the workflow I used.

I started with file preparation, followed by terminology extraction and MT + post-editing. After that, I ran two rounds of in-game testing, generated bug checklist, and iterated until all linguistic and technical issues were resolved.

Slide 3: Game Demo

Slide 4: Challenges — Linguistic, Creative & Technical Demands

A Dark Forest presented two categories of challenges.

1. Linguistic challenges

Localizing “A Dark Forest,” a text-driven adventure game, posed unique challenges due to its reliance on language for player immersion. Unlike visually-driven games, this project required precise attention to tone, wordplay, and style to preserve the narrative experience. After playing, I found that this game’s narrative style and wordplay diverged from typical D&D frameworks, making traditional fantasy termbase somewhat inadequate. Which means that I have to set up my own termbase.

2. Technical challenges

I initially struggled with the unfamiliar programming language GDScript and the Godot engine. Fortunately, I quickly realized that GDScript’s logic is very similar to Python, which made the whole development process much more manageable.

The project also lacked any centralized text management. Many strings were hard-coded across different scripts or embedded directly within game logic, which made it difficult to identify, extract, and maintain the content consistently. I had to manually locate all text assets throughout the project, extract them into an external structure, and rebuild a system that could support proper localization workflows.

Slide 5: Terminology Management

My approach goes like this:

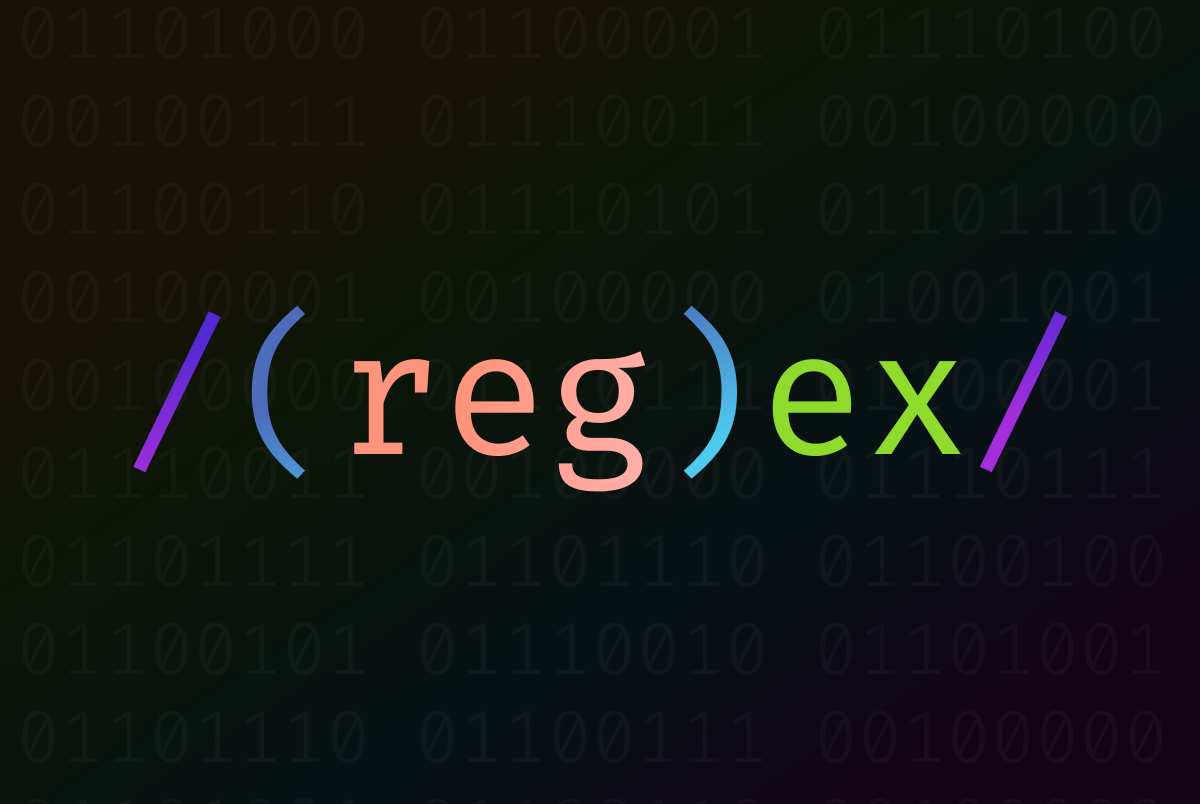

- Extract candidate terms from locale_en.gd using regular expressions to isolate text segments, NLTK tokenization, 1–3 gram generation and frequency counting

- Use AI to generate initial draft translations

- Manually review and refine all terms.

- Expand, delete, or revise terminology entries as new context appears during translation and QA.

Slide 6: Translation Process

- For the actual translation workflow, I used a MT + post-editing pipeline through Phrase.

- Machine translation for speed and broad coverage.

- Manual inspection using the termbase to ensure tone and consistency.

- In-game testing to surface real-context issues—especially dynamic strings.

- Manual polishing based on the error spreadsheet created during LQA.

Slide 7

During testing, I created a spreadsheet to log all linguistic and contextual issues found during gameplay.

These included:

- style inconsistencies

- untranslated strings

- UI overflow issues

Slide 8

- MT-generated unnatural expressions

Slide 9

- Text mismatches

Slide 10: Technical Solutions & Python Scripting

From here, I’ll walk through the technical backbone of the project—because automation was essential for dealing with such fragmented file structure.

Slide 11: File Analysis and Keyword Search

To start the localization process, I first needed to understand where all the text content lived inside the Godot project.

The game didn't have a centralized text system, so I used VS Code to analyze the folder structure and perform keyword searches across the entire repository.

By searching for in-game lines and UI terms, I identified the primary translation files, such as locale_en.gd, along with a large number of .tres resource files under the enemy_data, npc_event, and other directories.

These .tres files store attributes like enemy descriptions, flavor text, and various gameplay messages, but they weren’t organized for localization at all.

This step gave me a clear mapping of where translatable content existed and what needed to be extracted.

Slide 12: Batch Matching

Once I knew where the content lived, I built a Python script to automate the extraction.

The script recursively scans the entire source folder, checks each file for key fields such as text, flavor, and max_flavor, and then writes these values into a consolidated output file.

It also preserves the original directory structure, so I could later trace each line back to its source during reintegration or QA.

Slide 13: Batch Conversion

Godot’s .tres format isn’t compatible with CAT tools like Phrase, so I needed a way to transform these files into a format translators can actually work with.

This Python script recursively scans the project directory, finds all .tres files, renames and copies them into a parallel folder structure, and converts the extension to .txt.

This step allowed me to import all text assets into Phrase, run translation and QA there, and then later convert everything back into the .tres format for reintegration into the game.

Slide 14: Terminology Building

The script uses NLTK to tokenize the text, filter out stop words, and generate 1-gram, 2-gram, and 3-gram candidates.

It then counts their frequencies and exports everything into a CSV file.

Once I had this list, I used AI to perform an initial rough translation of each extracted term, which made it easier to identify key terminology and then finalize the term base manually.

Slide 15: Identify Untranslated Content

By searching for English keywords like “torch,” I could quickly see which lines had already been translated inside locale_en.gd and which occurrences still appeared in .tres or .tscn files.

VS Code’s global search made it very easy to scan through all resource files and UI screens, highlight untranslated segments, and ensure I didn’t miss any text hidden deep in the project.

Slide 16: Modify the Humanify Function

So on this slide, I want to talk about something called the Humanify function…

which, ironically, was not human-friendly at all when I first found it.

This function is used by the game to convert internal IDs directly into on-screen text without going through any language resources.

That means certain key terms—like “essence,” “spirit,” “cat,” or “singularity”—never passed through the localization system. They were just pulled straight from code and displayed to the player.

To fix this, I updated the Humanify function by adding a dictionary that maps these internal IDs to their localized equivalents.

So whenever the game tries to display one of these IDs, the function intercepts it and returns the correct localized term instead.

Slide 17: Further Optimization

Even after all the polishing and technical work, there are still one point that are open for further optimization.

The one is units — K, M, and B.

Right now, the game uses English-style abbreviations for numbers.

If I switch them to Chinese units like “万” or “亿,” the display becomes more natural for Chinese players.

However, this change affects visual balance of the interface, UI layout, spacing, and even some of the progression formulas.

Reflection: Engineering Challenges & Workflow Insights

Looking back at the entire workflow, the most valuable takeaway for me was realizing that localization engineering decisions compound quickly. A small architectural gap early on, such as the absence of a centralized text system—produced disproportionate complexity downstream. This experience reinforced that in any future localization project, I need to assess the technical foundations first and determine whether the existing architecture can support scalable localization. If it cannot, building the necessary infrastructure upfront is almost always cheaper than patching around it later.

Technically, the most significant surprise was how fragmented the translatable content was across Godot’s ecosystem. Even though the project was relatively small, but the huge amount words count (7000+), the combination of hard-coded strings, .tres resources, and script-embedded text meant that I had to effectively reverse-engineer the game’s content distribution before translation could even begin. That process reshaped the project’s scope and made me realize that localization engineering often behaves more like investigative work than pure implementation.

I also underestimated the engineering overhead required to make the content CAT-tool-friendly. Designing Python scripts to automate the whole workflow, normalize file formats, preserve directory structure, and reconstruct resource files after translation became a core part of the workflow, not an auxiliary step. This taught me that automation is not just a convenience, it is a prerequisite for reliability when dealing with decentralized game assets. Without the batch extraction and conversion scripts, consistency checking and reintegration would have been nearly impossible to manage manually.

Another insight came from debugging. Initially, I assumed the game’s display pipeline would route all text through locale files. Discovering that internal IDs bypassed the system entirely was a reminder that localization often exposes architectural shortcuts that are invisible during development. Refactoring the function to intercept ID calls and redirect them to localized terms reinforced my belief that localization engineering requires both Internationalization awareness and systems-level reasoning.

Lastly, integrating testing into the workflow earlier would have saved time. My first pass at translation surfaced numerous dynamic and context-dependent issues that only revealed themselves in gameplay. This reinforced a principle that applies to both software engineering and localization: context-driven QA cannot be deferred. In future projects, I plan to introduce round-trip testing much earlier—right after the first pass of extraction—to detect content logic gaps, UI collisions, and interaction-based strings before they accumulate.

Overall, this project sharpened my understanding of localization engineering as an intersection of text processing, automation, file architecture analysis, and system-level debugging. It also strengthened my belief that a strong engineering foundation is essential to preserving narrative quality in games.

Copyright Disclaimer: under section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976, allowance is made for “fair use” for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, education, and research. This project is a proof-of-concept, and as such does not represent nor infringe on the creator(s) in any way.